A War Correspondent's Story

(c) 2007, Bill Ryan

Bill McDougall and Frank Hewlett had much in common.

Both came from western towns only 150 miles apart; both had experience writing for newspapers; both craved the glamour and excitement of overseas work; and both wound up in 1940 as deskers for the English language Japan Times of Tokyo.

Seeing war was imminent, United Press was beefing up its Far East bureaus. Both men joined the wire service.

McDougall, 31, was sent to work with manager "Pepper" Martin in Shanghai.

Hewlett, 32, and his wife, Virginia, went to the Philippines, with Frank soon to serve as Manila bureau chief.

After war broke out and the Japanese advanced on Shanghai, Martin and McDougall eluded patrols and with the help of Chinese friends made it to safety.

McDougall was assigned to Java, where he missed the last plane to Australia by waiting to file "one last story," got on a ship which was sunk, nearly drowned, was captured on an island and spent the war in a high-mortality prison camp.

Hewlett’s coverage of the Japanese invasion of the Philippines won accolades.

In the six months between the outbreak of war and the fall of the Philippines, Hewlett spent much time with Gen. Jonathan Wainright, who succeeded Gen. Douglas MacArthur.

In his book, General Wainright’s Story, (Doubleday, 1946) he wrote, "There were a few close calls shared by my aides, Johnny Pugh and Tom Dooley, my orderly Sergeant (Tex) Carroll, and Frank Hewlett, the correspondent who often was with me.

"We were driving along one day, Hewlett and I, with Sergeant Carroll keeping his eye peeled looking for planes – when suddenly Carroll let out a Texas yell.

"The Filipino driver brought the car to a shrieking stop in the middle of the road and we threw open the doors. A Zero fighter was coming straight down the road at us, very low and tremendously fast.

"There were two little ditches at the side of the road. The driver hit the dirt on the opposite side of the road. Carroll dived into one of the ditches. Hewlett took a dry dive into the other ditch and I went in there on his back as the Zero’s wing guns opened up.

"The stream of bullets raced up the road at perhaps 300 mph and bit right through the top of (my) Packard.

"I got up off Hewlett’s back, feeling foolish. I hate to be a ground hog."

With little or no hope for the beleaguered garrison, Wainright later wrote, "It was about that time – when we fell back to what must have been our last position on Bataan – that my friend Frank Hewlett, the war correspondent, wrote the little tune that went:

We’re the battling bastards of Bataan,

No mama, no papa, no Uncle Sam,

No aunts, no uncles, no nephews, no nieces,

No rifles, no guns or artillery pieces,

And nobody gives a damn."

A typical Hewlett story, sent to the NX cables desk and run by newspapers around the world was this one:

JAP SNIPERS IN BATAAN HIDE BEHIND OWN PAINT

By Frank Hewlett

United Press

WITH GENERAL MACARTHUR’S ARMY IN THE PHILIPPINES -- Death in the form of bullets from the rifle of a green-painted Japanese sniper whizzed past my head today, and I’m shaking yet.

My experience with the sniper came when I accompanied Major Joseph Chabor and Major John Pugh to investigate a sector where a small group of Japanese had been cut off.

We were in sight of our destination when we stopped to talk with a Tank Corps lieutenant.

"Any snipers around?" asked Major Pugh.

"I haven’t heard of one on the trail," the lieutenant said. Just then a bullet kicked up the dust a foot from where we were grouped. Another whined past my ear, and then two more shots whizzed past.

Before the third and fourth shots came, however, the four of us had dived into the brush. We started squirming through the jungle floor flat on our bellies. It isn’t pleasant to burrow through that stuff, but you’re glad when there’s an enemy waiting to pick you off if yourself. When we were out of range we got to our feet again and compared notes. No one could agree where the shots came from.

Walking down these Bataan Peninsula trails where enemy snipers are lurking is like a boy walking past a graveyard on a dark night. Only you don’t dare whistle. You don’t dare run, either. Better crawl and jump from tree to tree. You’ll live longer, as three American Army officers and I discovered.

The snipers—nicknamed "the rattlesnakes of Bataan"—take particular pains to pick off officers. The one who shot at us was killed later. When we saw him we understood why we hadn’t even been able to determine where he was firing from.

He wore a green uniform that blended perfectly with the foliage of the high tree he had climbed. His face was painted green. His hands were green and he wore green shoes. He wore linesman’s climbers to aid in scaling the trees and his ammunition was smokeless.

Our sniper is still up that tree. He had tied himself to a limb and when an American rifleman picked him off his body remained high in the branches.

-30-

By March of 1942, hope for reinforcements died and American and Filipino forces retreated to Corregidor. Virginia Hewlett, a nurse, joined the other nurses in the military hospital on the island. She would spend the next 3 years there.

A brave pilot in a tiny two-seater plane made a series of landings on the bomb-pocked Corregidor air strip to ferry small amounts of food and medicine in and personnel out. That’s how Gen. Wainright arranged for Hewlett to escape to Australia to cover the Asian war for U.P.

Hewlett’s work was widely praised.

United Press ran this ad in the Dec. 16, 1944 issue of Editor & Publisher:

"It is a tale that should be put in scrapbooks

and read in schoolrooms," wrote one editor

among the many who commented on Frank

Hewlett’s report of the end of Bataan.

"Hewlett was in charge of the U.P. bureau in

Manila when war struck it three Decembers ago.

After his world-beat on the bombing of the un-

defended city, he crossed to Bataan in the last

car over the bridge. From there, as the only reg-

ular correspondent with the U.S. forces, he sent

for four months the news of their immortal stand.

The Headliner’s award for outstanding accom-

plishment was one tribute to his work.

"In mid-April 1942 a patched-up training

plane took Hewlett from Corregidor. In Australia,

in New Guinea, in Burma – he was the only civil-

ian correspondent with Merrill’s Marauders – he

continued his front-line reporting. In Honolulu

last October (1944), headed for a leave on the

American mainland he had not seen for seven

years, he heard of the coming Philippine inva-

sion, voluntarily headed back to cover it. He filed

the first dispatch from the Philippines since his

own two and a half years before. He is now at

Ormoc.

"Hewlett’s devotion to his work, his reportori-

al ability, his hardihood – are typical of the United

Press correspondents on every war front who are

bringing you the world’s best coverage of the

world’s biggest news."

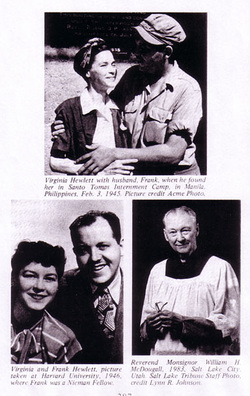

When the tide turned and Allied forces retook the Philippines, Hewlett was among the first to reach the prison on Corregidor and his wife. It was Feb. 3, 1945.

An Acme photo shows Hewlett in army fatigues with his arms around Virginia’s thin body just after he found her. Although she is smiling, she never recovered from the deprivations of prison life.

"My mother was sick, off and on the rest of her life because of her starvation," daughter Norma Jean Hewlett said recently.

Immediately after the war, Hewlett, like McDougall, spent an academic year at Harvard as a Nieman Fellow. He got in on the ground floor of the combined U.S. News & World Report.

He then settled his family in Virginia and for several years was the man in Washington for the Seattle Times, the Spokane Spokesman-Review, the Tulsa World, the Albuquerque Journal, the Honolulu Star-Bulletin and the Guam Daily News.

He became the Washington bureau chief of the Salt Lake Tribune in 1950, retiring in 1981.

While the Tribune’s rep, he was chairman of the Standing Committee of Correspondents, which sets the ground rules for covering Congress.

Virginia died in 1980. "My mother wanted her body to be donated for medical research," Norma Jean said.

Frank, 73, died July 7, 1983 in a Virginia hospital after a series of strokes. Because Virginia did not have a grave site, he chose to be buried in his hometown of Pocatello, Idaho, "To be near his relatives," his daughter said.

Officiating at graveside services for Frank, who was a Catholic, was his friend of more than 40 years and onetime Unipresser, Monsignor Bill McDougall of the Cathedral of the Madelene in Salt Lake City.

Norma Jean Hewlett said, "The publisher of the Salt Lake Tribune flew McDougall to Pocatello in his private plane" so both could be there.

McDougall concluded in his book By Eastern Windows, "Whether covering the news of war or the news of peace, Frank Hewlett was a gallant gentleman."

Bill McDougall and Frank Hewlett had much in common.

Both came from western towns only 150 miles apart; both had experience writing for newspapers; both craved the glamour and excitement of overseas work; and both wound up in 1940 as deskers for the English language Japan Times of Tokyo.

Seeing war was imminent, United Press was beefing up its Far East bureaus. Both men joined the wire service.

McDougall, 31, was sent to work with manager "Pepper" Martin in Shanghai.

Hewlett, 32, and his wife, Virginia, went to the Philippines, with Frank soon to serve as Manila bureau chief.

After war broke out and the Japanese advanced on Shanghai, Martin and McDougall eluded patrols and with the help of Chinese friends made it to safety.

McDougall was assigned to Java, where he missed the last plane to Australia by waiting to file "one last story," got on a ship which was sunk, nearly drowned, was captured on an island and spent the war in a high-mortality prison camp.

Hewlett’s coverage of the Japanese invasion of the Philippines won accolades.

In the six months between the outbreak of war and the fall of the Philippines, Hewlett spent much time with Gen. Jonathan Wainright, who succeeded Gen. Douglas MacArthur.

In his book, General Wainright’s Story, (Doubleday, 1946) he wrote, "There were a few close calls shared by my aides, Johnny Pugh and Tom Dooley, my orderly Sergeant (Tex) Carroll, and Frank Hewlett, the correspondent who often was with me.

"We were driving along one day, Hewlett and I, with Sergeant Carroll keeping his eye peeled looking for planes – when suddenly Carroll let out a Texas yell.

"The Filipino driver brought the car to a shrieking stop in the middle of the road and we threw open the doors. A Zero fighter was coming straight down the road at us, very low and tremendously fast.

"There were two little ditches at the side of the road. The driver hit the dirt on the opposite side of the road. Carroll dived into one of the ditches. Hewlett took a dry dive into the other ditch and I went in there on his back as the Zero’s wing guns opened up.

"The stream of bullets raced up the road at perhaps 300 mph and bit right through the top of (my) Packard.

"I got up off Hewlett’s back, feeling foolish. I hate to be a ground hog."

With little or no hope for the beleaguered garrison, Wainright later wrote, "It was about that time – when we fell back to what must have been our last position on Bataan – that my friend Frank Hewlett, the war correspondent, wrote the little tune that went:

We’re the battling bastards of Bataan,

No mama, no papa, no Uncle Sam,

No aunts, no uncles, no nephews, no nieces,

No rifles, no guns or artillery pieces,

And nobody gives a damn."

A typical Hewlett story, sent to the NX cables desk and run by newspapers around the world was this one:

JAP SNIPERS IN BATAAN HIDE BEHIND OWN PAINT

By Frank Hewlett

United Press

WITH GENERAL MACARTHUR’S ARMY IN THE PHILIPPINES -- Death in the form of bullets from the rifle of a green-painted Japanese sniper whizzed past my head today, and I’m shaking yet.

My experience with the sniper came when I accompanied Major Joseph Chabor and Major John Pugh to investigate a sector where a small group of Japanese had been cut off.

We were in sight of our destination when we stopped to talk with a Tank Corps lieutenant.

"Any snipers around?" asked Major Pugh.

"I haven’t heard of one on the trail," the lieutenant said. Just then a bullet kicked up the dust a foot from where we were grouped. Another whined past my ear, and then two more shots whizzed past.

Before the third and fourth shots came, however, the four of us had dived into the brush. We started squirming through the jungle floor flat on our bellies. It isn’t pleasant to burrow through that stuff, but you’re glad when there’s an enemy waiting to pick you off if yourself. When we were out of range we got to our feet again and compared notes. No one could agree where the shots came from.

Walking down these Bataan Peninsula trails where enemy snipers are lurking is like a boy walking past a graveyard on a dark night. Only you don’t dare whistle. You don’t dare run, either. Better crawl and jump from tree to tree. You’ll live longer, as three American Army officers and I discovered.

The snipers—nicknamed "the rattlesnakes of Bataan"—take particular pains to pick off officers. The one who shot at us was killed later. When we saw him we understood why we hadn’t even been able to determine where he was firing from.

He wore a green uniform that blended perfectly with the foliage of the high tree he had climbed. His face was painted green. His hands were green and he wore green shoes. He wore linesman’s climbers to aid in scaling the trees and his ammunition was smokeless.

Our sniper is still up that tree. He had tied himself to a limb and when an American rifleman picked him off his body remained high in the branches.

-30-

By March of 1942, hope for reinforcements died and American and Filipino forces retreated to Corregidor. Virginia Hewlett, a nurse, joined the other nurses in the military hospital on the island. She would spend the next 3 years there.

A brave pilot in a tiny two-seater plane made a series of landings on the bomb-pocked Corregidor air strip to ferry small amounts of food and medicine in and personnel out. That’s how Gen. Wainright arranged for Hewlett to escape to Australia to cover the Asian war for U.P.

Hewlett’s work was widely praised.

United Press ran this ad in the Dec. 16, 1944 issue of Editor & Publisher:

"It is a tale that should be put in scrapbooks

and read in schoolrooms," wrote one editor

among the many who commented on Frank

Hewlett’s report of the end of Bataan.

"Hewlett was in charge of the U.P. bureau in

Manila when war struck it three Decembers ago.

After his world-beat on the bombing of the un-

defended city, he crossed to Bataan in the last

car over the bridge. From there, as the only reg-

ular correspondent with the U.S. forces, he sent

for four months the news of their immortal stand.

The Headliner’s award for outstanding accom-

plishment was one tribute to his work.

"In mid-April 1942 a patched-up training

plane took Hewlett from Corregidor. In Australia,

in New Guinea, in Burma – he was the only civil-

ian correspondent with Merrill’s Marauders – he

continued his front-line reporting. In Honolulu

last October (1944), headed for a leave on the

American mainland he had not seen for seven

years, he heard of the coming Philippine inva-

sion, voluntarily headed back to cover it. He filed

the first dispatch from the Philippines since his

own two and a half years before. He is now at

Ormoc.

"Hewlett’s devotion to his work, his reportori-

al ability, his hardihood – are typical of the United

Press correspondents on every war front who are

bringing you the world’s best coverage of the

world’s biggest news."

When the tide turned and Allied forces retook the Philippines, Hewlett was among the first to reach the prison on Corregidor and his wife. It was Feb. 3, 1945.

An Acme photo shows Hewlett in army fatigues with his arms around Virginia’s thin body just after he found her. Although she is smiling, she never recovered from the deprivations of prison life.

"My mother was sick, off and on the rest of her life because of her starvation," daughter Norma Jean Hewlett said recently.

Immediately after the war, Hewlett, like McDougall, spent an academic year at Harvard as a Nieman Fellow. He got in on the ground floor of the combined U.S. News & World Report.

He then settled his family in Virginia and for several years was the man in Washington for the Seattle Times, the Spokane Spokesman-Review, the Tulsa World, the Albuquerque Journal, the Honolulu Star-Bulletin and the Guam Daily News.

He became the Washington bureau chief of the Salt Lake Tribune in 1950, retiring in 1981.

While the Tribune’s rep, he was chairman of the Standing Committee of Correspondents, which sets the ground rules for covering Congress.

Virginia died in 1980. "My mother wanted her body to be donated for medical research," Norma Jean said.

Frank, 73, died July 7, 1983 in a Virginia hospital after a series of strokes. Because Virginia did not have a grave site, he chose to be buried in his hometown of Pocatello, Idaho, "To be near his relatives," his daughter said.

Officiating at graveside services for Frank, who was a Catholic, was his friend of more than 40 years and onetime Unipresser, Monsignor Bill McDougall of the Cathedral of the Madelene in Salt Lake City.

Norma Jean Hewlett said, "The publisher of the Salt Lake Tribune flew McDougall to Pocatello in his private plane" so both could be there.

McDougall concluded in his book By Eastern Windows, "Whether covering the news of war or the news of peace, Frank Hewlett was a gallant gentleman."

Author Bill Ryan was born in Pocatello, Idaho in 1929. Working his way through college, he received a BA in 1952 from Idaho State University and received a master’s degree from Marquette University in 1957.

In 1955, he married Marguerite Phillips, a journalism major he met at Idaho State. They subsequently had four boys.

He served for four years as news director for a radio station in Pocatello while teaching speech courses at Idaho state and stringing for UPI.

In 1965 he was appointed Idaho State’s first full time alumni director. During his term he increased the school’s alumni rolls from 4,000 to 17,000.

Ryan was named assistant professor in Idaho State’s journalism department in 1971. When an opportunity opened with UPI, he moved his family to Dallas in 1977.

His UPI career ended when he retired in 1994. He has since done much writing for various publications.

In 1955, he married Marguerite Phillips, a journalism major he met at Idaho State. They subsequently had four boys.

He served for four years as news director for a radio station in Pocatello while teaching speech courses at Idaho state and stringing for UPI.

In 1965 he was appointed Idaho State’s first full time alumni director. During his term he increased the school’s alumni rolls from 4,000 to 17,000.

Ryan was named assistant professor in Idaho State’s journalism department in 1971. When an opportunity opened with UPI, he moved his family to Dallas in 1977.

His UPI career ended when he retired in 1994. He has since done much writing for various publications.