A History of United Press International Newspictures Service

United Press editor Lucien Carr, whose roommate Jack Kerouac wrote On the Road using a roll of teletype paper swiped from a UP office, once said, "UP's great virtue was that we were the little guy [that] could screw the AP."

(That manuscript, 119 feet long with no paragraphs or page breaks, fetched $2,200,000 at Christie’s auction in May 2001, a record price for a literary work. Kerouac had noted in pencil on the manuscript that Carr’s dog “ate” his last few sentences.) (SEE NOTE AT BOTTOM OF THIS PAGE)

E. W. Scripps (1854-1926) created the first chain of newspapers in the United States and then created his own news service, United Press Association, in 1907 after the Associated Press refused to sell its services to several of his papers. Scripps believed that there should be no restrictions on who could buy news from a news service, and he made UP available to anyone, including his competitors.

The AP was owned by its newspaper members who could simply decline to serve the competition. Scripps had refused to become a member of AP.. A “monopoly pure and simple,” he fumed, making it “ impossible for any new paper to be started in any of the cities where there were AP members.”

“AP” first appeared in 1848 when six New York newspapers formed a cooperative to gather and share telegraph news, but the name Associated Press did not come into general use until the 1860s. United Press became the only privately owned major news service in the world at a time the world news scene was dominated by the Associated Press in the United States and by the news agencies abroad, which were controlled directly or indirectly by their respective governments: Reuters in Britain, Havas in France, and Wolff in Germany. William Randolph Hearst entered the fray in 1909 when he founded International News Service.

(That manuscript, 119 feet long with no paragraphs or page breaks, fetched $2,200,000 at Christie’s auction in May 2001, a record price for a literary work. Kerouac had noted in pencil on the manuscript that Carr’s dog “ate” his last few sentences.) (SEE NOTE AT BOTTOM OF THIS PAGE)

E. W. Scripps (1854-1926) created the first chain of newspapers in the United States and then created his own news service, United Press Association, in 1907 after the Associated Press refused to sell its services to several of his papers. Scripps believed that there should be no restrictions on who could buy news from a news service, and he made UP available to anyone, including his competitors.

The AP was owned by its newspaper members who could simply decline to serve the competition. Scripps had refused to become a member of AP.. A “monopoly pure and simple,” he fumed, making it “ impossible for any new paper to be started in any of the cities where there were AP members.”

“AP” first appeared in 1848 when six New York newspapers formed a cooperative to gather and share telegraph news, but the name Associated Press did not come into general use until the 1860s. United Press became the only privately owned major news service in the world at a time the world news scene was dominated by the Associated Press in the United States and by the news agencies abroad, which were controlled directly or indirectly by their respective governments: Reuters in Britain, Havas in France, and Wolff in Germany. William Randolph Hearst entered the fray in 1909 when he founded International News Service.

Read more about UPI Newspictures

By the early 1900s the U.S. had almost 2000 newspapers, and there was growing awareness among them that pictures helped sell newspapers, which helps sell more advertising. Large New York papers began to publish separate Sunday sections full of pictures, and in 1919 New York's first tabloid, the Illustrated Daily News, advertised itself as “The Picture Paper" and featured pictures over words. By 1924 circulation had reached nearly a million copies a day.

Newspapers and magazines had staff photographers, but also relied on Hearst's International News Photos (INP), Scripp's Acme newsphotos, and AP, in 1927, to provide photos throughout the U.S. and the world. The news agencies relied heavily on photos they bought from other sources, and a considerable number of AP’s pre-Wirephoto pictures were prints made from 35mm frames from Paramount Pictures’ newsreels. No movie theater program was complete in those pre-TV days without a newsreel shown just before the main attraction. The silver screen lit up with the week’s heroes and heroines, fads and fashions, disasters and triumphs of the era, a rich trove of material for AP.

UP had no photo service until 1952, when it absorbed Acme, run by Robert Dorman, who Scripps executive Boyd Lewis described as a “former swashbuckler and gun runner. ” A Runyonesque character, he had ridden as a reporter with Pancho Villa in Mexico, clung to rickety planes in the Arctic, and bounced across the plains in chartered trains trying get the best pictures out first. Dorman favored cigars and good bourbon, and kept a bottle handy in the office to entice his staff to stick around after work for late-night poker games. His second in command was Harold Blumenfeld.

Words were being transmitted over phone lines long before anybody came up with reliable and economical machines that could send and receive pictures that way. Early experiments at sending photos by wire were “point to point,” a transmitter connected by phone line to a single receiver.In 1924 Dr. Herbert Ives of Bell Labs demonstrated an experimental “telephotography” machine that a year later AT&T used7URH6Y to send a photo of Calvin Coolidge being sworn in as President to newspapers in three cities simultaneously. AT&T was publicizing its new commercial “telephotograph” service in eight cities, hoping to attract customers who wanted to send documents and signatures by wire, but it never caught on.

Only on rare occasions would Acme or AP send “telephotographs” because even after the hour it took to send one, a recognizable image did not always appear at the receiving end.One editor complained that wired photos “fail as yet to register recognizable features" though most editors in those early days didn’t grasp the fact that even a poor-quality photo transmission brought their readers immediate visual information from distant places that could be obtained no other way.Admitting in 1928 that “a considerable proportion of the telephotographs have to be retransmitted because of lightning, static, and other troubles” AT&T abandoned their its first system altogether in 1933, having invested $2.8 million trying to get it to work.

In the works at Bell Labs, however, was a second-generation “picture sending apparatus" of an entirely different design, using all-new technology, that Bell claimed would transmit pictures faster and deliver copies “indistinguishable from the transmitted original.” But well into the 1930s, the picture agencies still were sending their photos to clients by auto, train, airplane, bicycle, or any means available, a built-in delay of hours and even days.The news photo services were still in a three-cornered fight though 1934, when AP startled its competitors by announcing what it called a $1,000,000-a-year Wirephoto system. It claimed that soon, AP newspictures would be in its client’s hands only hours after they were made. No start date was announced.

Not long after AP's announcement, the luxury liner Morro Castle flashed an SOS on September 8, 1934, from just six miles off the New Jersey coast. The ship was ablaze, her captain dead of mysterious causes, and a terrible storm raged. The ship’s firefighting equipment had been shut off. 131 passengers and crew would perish.Cautious air charter pilots stay grounded in vile weather, but International and Acme knew pilots with daring and courage who would fly - if the payment was generous enough - through just about anything. At dawn in two separate planes, INP and Acme photographers flew over the doomed ship and got dramatic pictures. AP had no pictures of the burning vessel and Acme and INP wanted to make sure everybody knew it.

Soon trade paper ads compared their aerial photos of the burning liner to the file photo AP offered of the ship in port well before the calamity, under a headline that mocked AP: YOU MUST FIRST GET THE PICTURE BEFORE YOU NEED A MILLION DOLLAR TELEPHOTO.

New Year’s Day, 1935, was literally the dawn of the “picture wire service,” and the most significant date yet in news photography’s coming of age in the United States. The Associated Press had adopted the AT&T system and inaugurated “Wirephoto.”

Invited guests were on hand to witness the birth of Wirephoto, which could carry high-fidelity pictures to multiple receivers over a national leased phone network. Solemn engineers tweaked dials and tinkered with an eight-foot panel full of bulbs, wires, and wavering needles.In 24 newspaper offices across the country other guests watched technicians tinker with switches, generators, and lathe-like receivers. Lights flashed, needles swung, and then a whistle blew. A stentorian voice over a loudspeaker announced: "New York speaking. This will be the first official roll call for Wirephoto."That first picture showed half-frozen survivors of a plane crash deep in the Adirondack Mountains, and the 24 papers received it simultaneously on a 10,000-mile leased circuit, proof that photographs, not just words, could be delivered by wire.

News photography, at last, was catching up with print. Editors suddenly had both words and pictures of that same day’s events, and readers could see what was happening in the world at the same time they read about it. Editor & Publisher magazine that year began a regular column devoted to news photography. In his first column Jack Price wrote, "The snobbishness of the scribe towards the photographer is fast disappearing. Photography has a very definite place in modern journalism."Any of AP’s 1,200 members could have Wirephoto if they shared its costs, based on their city’s population. In New York in 1936, Wirephoto cost $150,000 a year, and only one of New York’s eight daily newspapers, the tabloid Daily News, thought it worth the investment. Every paper on the leased photo network could transmit as well as receive photos, enabling them to share their own best pictures with other AP member papers on the “party line” leased telephone circuit. By March 1935 Wirephoto was carrying about 70 pictures a day.

Conspiculously absent from the new Wirephoto network were Hearst and Scripps-Howard newspapers, although fifteen of Hearst’s papers and six of Scripps Howard’s were AP members. Publisher Roy Howard had lobbied against the Wirephoto project at AP’s annual meeting. AP's general manager Kent Cooper was the force behind AP's launch of a photo service in 1928, and now, he was pushing the newest photo delivery technology on a skeptical AP membership. Both Hearst and Howard huffed that wirephoto would be a needless extravagance, and sure to lead to ruinous competition, all for the sake of "pulling A. T. & T.'s $2,800,000 chestnut out of the fire."The Scripps and Hearst organizations, as well as Wide World, owned by The New York Times, had been working on their own photo transmitting and receiving machines since AP’s announcement in 1934. INP called theirs "Soundphoto," Acme was "Telephoto;” Wide World was "Wired photo."

A January 1936 AP advertisement in Editor and Publisher magazine rhapsodized about Wirephoto’s first year: “Eighteen thousand pictures, traveling 180 million miles, made it possible for the news-hungry public to see, with the keen eyes of the camera that misses no detail, the what and how and why of everything that was news while it was news. The result of a year of Wirephoto is a new kind of reporter, a newsman trained to see news in terms of pictures which can be delivered an hour from now instead of tomorrow, or next day.”

Before its own electronic delivery system was up and running Acme tried to stay in the game by using airplanes to deliver its pictures. And two things things bought the company time. AP’s photo reception quality sometimes left much to the imagination. And Acme’s Fred Ferguson had scored a coup when he secured exclusive rights to all photographs taken of the Dionne Quintuplets, born in 1934, through their fifth birthday.The five cute, identical girls, the first quints known to have survived from birth, had grabbed the world’s attention. They drew more visitors to Canada than Niagara Falls, and offered an upbeat distraction in the depths of the Great Depression. The public loved quint pictures, and only Acme could provide them, so editors retained Acme’s photo service while the company perfected its own photo transmitter/receiver equipment.

By the time quint fever abated in 1936, Acme had developed its own picture machines, more sophisticated and reliable than AP’s, and capable of better quality. Photos were transmitted to subscribers on a limited basis, and “Telephoto” was put through a successful test at the 1936 political nominating conventions in Philadelphia and Cleveland.Three major photo services were still slugging it out in 1948, when Acme, AP, and INP assembled crews in Philadelphia for the Democratic National Convention. Harold Blumenfeld, always thinking "speed," located Acme’s workroom right inside the convention hall, enabling Acme to put pictures in client hands less than 30 minutes after they were taken. AP and INP were slowed because they had located workrooms off-site. AP at The Philadelphia Bulletin, a mile and a half away, and Hearst’s INP at the University of Pennsylvania, a quarter mile away.

AP and INP’s response was stopped cold for awhile after President Harry Truman arrived at the hall and the Secret Service locked down the building for a time, making it impossible for AP and INP film messengers to even get film out of the hall.Dick Sarno, head of Hearst’s INP picture operation, was so impressed with Acme’s quick turnaround time that he appeared at Acme’s door to ask Blumenfeld if William Randolph Hearst, Jr., could come see how they did it. Young Hearst got a guided tour.In 1951 Scripps president Roy Howard persuaded a reluctant United Press management to make 27-year old Acme Newspictures a part of UP, to better match pictures and words and more smoothly compete against AP. UP president Hugh Baillie had resisted such a move for years, fearing that establishing a network of picture bureaus would diminish UP’s profits. Boyd Lewis later wrote, “The UP, which should have [been competing] on even terms with AP, had declared dividends for its executives for years -- by avoiding picture investment.”

Mims Thomason was named UP Newspictures general manager and Frank Tremaine, a distinguished reporter and editor, the assistant GM. “I didn’t even own a camera,” Tremaine says. “So there we were – two amateurs thrown in on top of a bunch of pros. It took a while for [word] Unipressers around the world to accept pix people as one of them.”The new United Press picture network was not as extensive as AP’s, and expanding it across the country became a top priority. A pair of brilliant UP engineers, Jerry Callahan and John Long, came up with Unifax in 1954, a revolutionary machine that needed no operator. Pictures could be viewed as they came in on a continuous roll of inexpensive electrolytic paper. Suddenly UP’s picture service was within economic reach of the country’s smallest newspapers and television stations. Unifax would soon bring UP pictures into 400 cities, allowing UPI to expand its leased photo network, and fill the great gaps between the East and West coasts.

Frank Bartholomew, UPI's last reporter-president, took over in 1955 obsessed with bringing Hearst's International News Service (INS) into UP. He put the “I” in UPI in the spring of 1958, when UP and INS merged to become United Press International. (UPI).Hearst, who owned King Features Syndicate, received a small share of the merged company. Lawyers on both sides worried about antitrust problems if King competitor, United Features Syndicate, remained as a part of the newly merged company. So UFS was made a separate Scripps company, which deprived UPI of a persuasive sales tool and the eventual river of gold generated by Charles Schulz’ wildly popular Peanuts and other comics.

The new UPI now had 6,000 employees and 5,000 subscribers, 1,000 of them newspapers, though a decline in the number of the country’s newspapers had begun. In cities that had two or more papers, the afternoon dailies, a majority of them UPI clients, were often the first to throw in the towel. There was also stiff new competition from “supplemental” news services created by major newspapers, including The New York Times and The Chicago Tribune,which had begun marketing their own news content to other news organizations at bargain-basement prices. AP was a publishers' cooperative and could “assess” its members to help pay for extraordinary coverage of such things as wars, the Olympic Games, or national political conventions. But UPI clients paid only a fixed annual rate; they expected UPI to cover extraordinary events but UPI couldn’t ask them to help shoulder the extraordinary coverage costs.

UPI sold its services helter-skelter, charging clients what they were willing to pay instead of basing rates on the size of the paper’s market in twenty three of the largest U.S. cities. Newspapers typically paid UP about half what they paid AP in the same cities for the same services. The Chicago Sun-Times paid AP $12,500 a week but UPI only $5,000; the Wall Street Journal paid AP $36,000 a week but UPI only $19,300. Most papers paid less for UPI’s worldwide news and photo services than the salary they paid just one staff reporter.

Though UPI never faltered as a news powerhouse, it needed management and financial support from Scripps that it didn’t get. As UPI’s losses grew, Scripps focused on containing the losses instead of exploring new revenue sources. “The only bank we could do business with was Scripps,” former UPI president Rod Beaton told an interviewer in 1995. “They had one vision. UPI was to be a fully competitive alternative news service to the Associated Press.“[Scripps] wanted UPI for their newspapers and for their broadcast stations, period,” Beaton said. “ Beyond that, they weren't interested. The business was changing rapidly, so fast that we couldn't keep up with it. Hell's bells, we should have been the CNN.

There wasn't a way in hell we could do that as long as Jack Howard was on our board. Jack represented the broadcast interests of Scripps, and they didn’t want us doing that, period. Our ownership limited our opportunities sometimes.”Both Beaton and Charles Scripps, however, ignored entreaties from Bernard Townsend, a Scripps financial vice president, to explore the growing world market for business and financial information. UPI stuck to its basic business as the media landscape shifted and more nimble media companies found ways to profit from the communications revolution - a market that would enrich rival Reuters.UPI lost $5.3 million in 1978, and Scripps began looking for someone to take the company off its hands. The client list was robust, with 7,079 subscribers worldwide, including 1,134 newspapers and other publications and 3,699 broadcasters in the U.S. Scripps looked first to the journalism community, but the big players - among them The New York Times and the Times-Mirror and Knight Ridder chains – all said their shareholders would not want them investing in an ailing enterprise. News organizations that benefitted most from the fierce competition between two news services proved unwilling to help keep one of them in business.

E. W. Scripps had established a trust for his four oldest grandchildren, and by 1981 all were in their 60s. If Scripps simply folded UPI, the trust could face as much as $50 million in severance pay, pensions, and other costs. But if they continued to underwrite UPI’s heavy losses the trustees could be open to lawsuits by the heirs.Like washing and waxing a car before a sale so the customer doesn’t look too closely under the hood, Scripps even spiffed up UPI’s New York headquarters to impress would-be buyers. The news and photo departments were relocated and the first new furniture staffers had seen in years appeared, along with workstation cubicles that made UPI’s world headquarters resemble an insurance office. No longer could anyone eat lunch at their desk – but that policy was dropped when staffers actually started leaving their desks for lunch and their phones and the day’s business went unattended until their return.Reuters, a British-owned news agency, ran a limited newsgathering operation in the United States. Sensing a bargain, Reuters expressed interest in UPI, and its executives toured bureaus in the US and abroad, gaining intimate knowledge of UPI operations, before talks collapsed. But Reuters would be back. By 1982, after four years of trying to find someone to take UPI off their hands, the Scripps family members reached the end of their rope. They even considered giving the company to National Public Radio, which could have meant a UPI tax break for as much as $100 million. NPR nixed the idea. The company’s financial troubles seemed irreversible, and “ UPI had become such a hot potato,” one executive said, “that they were ready to toss it to anyone who would grab it." Grab it, someone did. On June 2, 1982, Scripps president Ed Estlow announced that UPI had been sold, to Media News Corp., a new company formed by an unlikely and virtually unknown pair of young entrepreneurs from Tennessee. Doug Ruhe, 37, and Bill Geissler, 35. They owned a small Nashville company that, it turned out, was barely meeting its payroll, an attribute they'd bring with them to UPI.

The two men had no news experience, and in time they managed to do to UPI what AP could never have accomplished – pillage the company assets and reduce a proud company to insignificance. Over the next 17 years after UPI was "sold" it would have four chairmen, 13 presidents, a fire sale of assets, ever-shrinking revenues, and a steady defection of clients. And twice it would seek bankruptcy protection.

Ultimately, and contrary to speculation at the time, Scripps didn't get even one dollar for UPI; it gave UPI away, and sweetened the deal by giving the new owners eight million dollars to pay off debts and shore up the anemic pension fund. “In a sense,” Charles Scripps later said, “we filled up the gas tank and sold it that way. So they had some working capital.”Scripps wanted no liability if UPI’s creditors forced the company into bankruptcy, and wanted to demonstrate that it had made every effort to give the new owners a reasonable chance at success. “It was not generosity as much as self-interest,” a source close to the negotiations said. “The main consideration was that Scripps didn’t want to get the business back in six months.”

Soon there were hints of money troubles. In 1983 UPI president Bill Small got a call from a friend, a vice president of The Chicago Tribune, wondering why UPI hadn’t paid the $100 owed for papers delivered to UPI’s Chicago bureau. By 1984 money was so tight that the phone company cut off bureau telephones for nonpayment.Ruhe and Geisler weren’t exactly wowing the journalism world. They had owned UPI for a year and a half when they tried to “wing it” in a forum where newspaper experience and maybe doing some homework would have been helpful: their debut before the convention of the American Society of Newspaper Editors.They did not invite any of their older and wiser UPI veterans onstage to help field questions. Will Jarrett of The Denver Post got right to the point: “What can you provide newspaper editors that AP cannot?” Neither Ruhe or Geissler, separately or together, could offer a good answer. The New York Times coverage was merciless: “without exception editors interviewed after the session were convinced that Mr. Ruhe and Mr. Geissler did not know enough about newspapers to make it worthwhile to subscribe to the [UPI] service.” Photo stringers helping UPI cover the 1984 Olympic Games in Los Angeles were surprised when a well-dressed fellow appeared, carrying a briefcase full of money to pay them in cash. Banks were no longer honoring UPI checks. Stringer Wade Byers remembers being told that “The owners were trying to sell UPI and it would send the wrong message if the company collapsed during the Olympic Games.”Other stringers around the country weren’t so lucky. They continued to provide pictures that UPI used immediately and submitted bills that UPI didn’t pay for weeks or months. Fed up with the long wait, many drifted away to the competition. Staffers had it slightly better:their paychecks still cashed, but UPI was slow to reimburse them for out-of-pocket expenses – cabs, meals, and such. American Express canceled cards issued to executives and bureau chiefs. UPI had come to stand for “UnPaidInvoice.”

UPI was so desparate for cash – in many cases barely able to meet the payroll – that Doug Ruuhe began selling off irreplaceable parts of UPI at fire-sale prices.

Assets UPI needed to sustain day-to-day operations were sold for less than the annual revenues they produced: the company’s stake in UNICOM, a worldwide commodities news service; its right to one-fourth interest in UPITN, a television news film service; the rights to its electronic data base; the right to market UPI’s stock price reporting service; and its priceless, 11.5-million image picture library. These transactions provided one-time cash infusions of millions of dollars but divested UPI of vital resources and revenues it needed to survive.

Perhaps the most capricious of all the dealmaking was the 1984 sale of UPI’s robust overseas picture operation to rival Reuters for about a third of what it was worth. So formidable was UPI’s European photo operation that UPI wouldn’t sell the picture service to any client who didn’t buy the news report, too.

Only a year before Ruhe had agreed when his senior staff told him that the foreign newspicture operation was so critical to UPI that it should be sold only as an act of desperation. Reuters had no photo operation of its own, and had predicted in a June 1984 stock-offering prospectus that it might acquire UPI's overseas operation for $7.5 million. Now, keeping the negotiations secret from even his most trusted executives, Ruhe sold the UPI foreign photo operation to Reuters for only 5.7 million, millions less than even Reuters thought they might have to pay just months earlier: $3.3 million in cash and $2.4 million in monthly payments over five years.The deal gave Reuters 24 functioning photo bureaus and dozens of its best photographers, plus a working distribution system and millions of dollars in long-term client contracts. It enabled Reuters to take a giant leap ahead of Agence France-Press, which at the time was trying to organize its own worldwide photo service. European controller, Charles Curmi, had learned that Reuters might have been prepared to pay far more for UPI, perhaps as much as $10 million. He relayed that information to Ruhe’s negotiator, Bill Alhauser, who warned him not to rock the boat since UPI was so desperate for cash. The deal done, UPI’s executive picture editor.Ted Majeski, was outraged. “If there was a buck in it,” he said, “these guys would cut off and sell your leg and still expect you to run in the Olympics.”UPI would later claim that its ledgers weren’t sophisticated enough to determine whether the overseas picture operation had been independently profitable. But Mike Hughes, the UPI executive editor and vice president in charge of the international division, had no doubts. The sale to Reuters, he said, was “the most idiotic deal that was ever made."

Had Reuters worked 24/7 to organize its own service, Hughes said, “it would have taken (them) three years just to put all the transmitters in place. I'd say a conservative guess is that we saved them $20 million and five years." UPI, of course, still needed to provide foreign photo coverage for its domestic network. It could no longer direct foreign coverage or tailor it to UPI's needs. Using UPI’s former staffers, Reuters wouild now be provider of European photos to UPI. And as a part of the deal, UPI would furnish American photos to Reuters. In the final moments of negotiation Ruhe even agreed – against the anguished advice of key executives - to let Reuters compete with UPI in the U.S., selling its own photos to the larger U.S. newspapers. Majeski was openly contemptuous of Reuters’ ability to serve UPI’s needs. A major earthquake rocked Mexico City in 1985, and UPI was almost three hours ahead of AP with the story, but Reuters had not yet provided pictures. Majeski arranged a chartered plane and sent a photographer to Mexico City, who got sensational earthquake pictures for UPI clients. Majeski sent Reuters a bill for the charter.

Next on the block was UPI’s crown jewel: the picture library. Its 11.5 million images of events and personalities, some so old they were on glass plates, dated back to the Civil War. It is a priceless collection not just because of its size, but because of the “you are there” quality of its once-in-a-lifetime moments recorded by International Newsphotos (1912-58); Acme Newspictures (1923-52); Pacific and Atlantic Photos (1927-30) and United Press. The sale of reprint rights to the pictures was earning UPI more than a million dollars a year, using only four salesmen and no marketing program. The business department believed that a new electronic retrieval system and a marketing plan could double or triple that income. “Who cares about a damn picture library?” Geissler asked. In 1984 he sold it to the Bettman photo collection – by then owned by Kraus-Thompson of Canada - for only $1.1 million. It was called an “advance royalty payment” in a 20-year deal. Bettman gained exclusive control and proceeded to move the photo files UPI needed every day to Bettman’s New York office on 21st Street. UPI lost immediate access to its own archive and had to pay Bettman $35 every time it needed a copy of one of its own pictures, often several times a day. For a time it even charged UPI photographers $15 a print whenever they needed a print of one of their own photos to enter in year-end contests. Bettman split resales of UPI’s pictures, keeping 75 percent for itself. The owners needed cash. They seemed not to understand or care that they were selling a photographic treasure, although it is not difficult to imagine that the photo collection could have gone the way of UPI’s word files, which were sent to a warehouse and, after UPI failed to pay the rent, vanished, along with the warehouse. In 1966 a staffer visited the site and found an apartment building where the warehouse used to be.The fire sale of company assets had raised $10 million but in the process had reduced the company's annual revenuues by at least $7 million a year -- to $93 million a year from more than $100 million. UPI photo editor Ed Hart was assigned as liaison to Bettman after the move. The Bettman staff, he recalls, couldn’t grasp the meaning of UPI’s connection to the files. Bettman had never been a news service, and the Bettman staff was "totally unprepared to handle UPI’s requests for copies of its own pictures,” Hart says. “It was an adversarial relationship.” When the Duchess of Windsor died in 1968 and UPI needed a quick file portrait it couldn’t obtain one for six hours because Bettman’s overnight staffer wouldn’t let a UPI staffer come select one. Next day the Bettman staffer was fired.

In 1995 Bill Gates’ Corbis bought and is today preserving the Bettman archive – UPI’s 11.5 million images and the 5 million-plus pictures Bettman had accumulated since 1933. The undisclosed price was reported by Newsweek to be $6 million.While the company struggled to stay in business and UPI's loyal staff accepted a 25 per cent wage cut to help out, Ruhe and Geisler were hiring expensive consultants who did little but collect fees as high as $20,000 a month. The staff would have been scandalized to learn that the owners expecting them to make one sacrifice after another were paying a consultant more every six weeks than they made in a year. When UPI filed for bankruptcy in 1985 the court learned that UPI had collected employee payroll deductions, but had not forwarded them to the Internal Revenue Service or the employee credit union. In August 1990, many UPI staffers, including several senior editors, got pink slips, Senior executive Pieter VanBennekom sent a message to all bureaus. He would “miss those who left us,[but that] reshaping the staff is necessary to create the new UPI.” By November, saying it was on “life support, ” UPI imposed a 35% cut for remaining non-union employees. Staffers represented by the Wire Service Guild voted to accept the 35% wage cuts while, the Guild noted, “UPI tries to seek a buyer to keep the company alive.” By 1991, UPI was back in bankruptcy court, listing $22.7 million in assets but $65.2 million in liabilities.In 1998, Arnaud de Borchgrave, the former editor of the Reverend Sun Myung Moon's Washington Times, became UPI’s CEO, but by then UPI had lost virtually all its newspaper clients. It had retained some 400 radio clients, but in 1999 sold those contracts, too, to the AP.

By 1999 UPI ceased being a traditional wire service. "It is time to move on," Borchgrave said, and UPI would from that day forth exist only on the Internet. ”The world no longer needed two redundant wire services." In May 2000 what remained of UPI was sold to Moon’s News World Communications for an undisclosed amount. UPI was down to 157 employees -- in Washington, London, Latin America, and Asia – and only a few customers. Given the fact that Scripps gave the company away, one might wonder why UPI’s executives – who possessed the news experience Ruhe and Geissler lacked – didn’t try to buy UPI in 1982 when Scripps was paying someone to take the company off their hands. And if Scripps wanted to give the company away, why they didn't sound out UPI's loyal employees.Buying UPI, Frank Tremaine says, “was totally impractical financially. Even though the price was right, it took oodles of money to operate UPI and none of the top brass, which presumably included me, had the necessary resources.

The E. W. Scripps organization had sunk millions into the company to keep UPI afloat for years. They couldn't continue to do that, nor could they finance UPI executives to try to keep it going. Major publishers and broadcasters already had rejected the idea. It just wasn't feasible.”Bob Page said: “My regret, looking back on it, if I had known about leveraged buyouts, I would have put a group together. I said to Rod [Rod Beaton, UPI’s president] many times over that if they were going to give it away, which they did to Geissler and Ruhe, they should have given it to you and me. We wouldn't have screwed it up. I mean, we loved the company. They could have given it to all of us.” Today, the only mention of “UPI” in newspapers is likely to be found in the obituaries, since a considerable number of the nation’s journalists over 50 once worked for United Press International. “UPI never admitted to "going away," recalls photo stringer Harrison McClary. “They were still there, but from late 1993 or so anyone crazy enough to transmit (pictures) to them was not getting paid. They closed down most of their bureaus … and the people now working for them are not the same people from the old days” The decline of the once-great company “was like watching a parent die,” Ed Hart says, “From the time I was 17 years old, Acme, UP, and UPI was my family. I spent more hours with those people than I did at home.”

**6/2007 HAYNES' NOTE: KEROUAC'S USE OF UPI TELETYPE PAPER HAS BEEN CONFIRMED BY THREE INDEPENDENT SOURCES, DESPITE SEVERAL WEBSITES DESCRIBING THE MANUSCRIPT HAVING BEEN WRITTEN ON VARIOUS OTHER MATERIALS BY RESEARCHERS WHO LIKELY HAD NEVER SEEN, OR COULD NOT GRASP, THE CONCEPT OF A CONTINUOUS ROLL OF UPI TELETYPE PAPER.

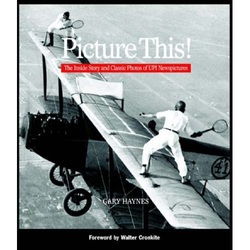

Text excerpted with permission from Picture This! The Inside Story and Classic Photos ofUPI Newspictures, (c) 2006, Gary Haynes

A special thanks to Ed Hart for permission to reproduce historical photographs accompanying this article.

Note supplied by Ed Hart: Author Gary Haynes' date for the creation of Pacific & Altnatic Photos (1927) is incorrect. P&A, the offspring of the New York Daily News and the Chicago Tribune, was in business in 1925. The photo that accompanies Haynes' article that shows P&A staffers at a Christmas Eve party has the earlier date written on the print itself and that information was put there by my father moments after he made the print in the late afternoon of Dec. 24, 1925. Later, that date was independently confirmed by two of the staffers identified in the party photo caption. Haynes relied on Frank Tremaine for the start-up date but Frank never worked for P&A, Haynes ckaimns FT had a story from the New York Times with the '27 date but the New York Times never worked for P&A, either. Besides, P&A negtive captions now a part of the Corbis photo library also confirm the earlier date.

Newspapers and magazines had staff photographers, but also relied on Hearst's International News Photos (INP), Scripp's Acme newsphotos, and AP, in 1927, to provide photos throughout the U.S. and the world. The news agencies relied heavily on photos they bought from other sources, and a considerable number of AP’s pre-Wirephoto pictures were prints made from 35mm frames from Paramount Pictures’ newsreels. No movie theater program was complete in those pre-TV days without a newsreel shown just before the main attraction. The silver screen lit up with the week’s heroes and heroines, fads and fashions, disasters and triumphs of the era, a rich trove of material for AP.

UP had no photo service until 1952, when it absorbed Acme, run by Robert Dorman, who Scripps executive Boyd Lewis described as a “former swashbuckler and gun runner. ” A Runyonesque character, he had ridden as a reporter with Pancho Villa in Mexico, clung to rickety planes in the Arctic, and bounced across the plains in chartered trains trying get the best pictures out first. Dorman favored cigars and good bourbon, and kept a bottle handy in the office to entice his staff to stick around after work for late-night poker games. His second in command was Harold Blumenfeld.

Words were being transmitted over phone lines long before anybody came up with reliable and economical machines that could send and receive pictures that way. Early experiments at sending photos by wire were “point to point,” a transmitter connected by phone line to a single receiver.In 1924 Dr. Herbert Ives of Bell Labs demonstrated an experimental “telephotography” machine that a year later AT&T used7URH6Y to send a photo of Calvin Coolidge being sworn in as President to newspapers in three cities simultaneously. AT&T was publicizing its new commercial “telephotograph” service in eight cities, hoping to attract customers who wanted to send documents and signatures by wire, but it never caught on.

Only on rare occasions would Acme or AP send “telephotographs” because even after the hour it took to send one, a recognizable image did not always appear at the receiving end.One editor complained that wired photos “fail as yet to register recognizable features" though most editors in those early days didn’t grasp the fact that even a poor-quality photo transmission brought their readers immediate visual information from distant places that could be obtained no other way.Admitting in 1928 that “a considerable proportion of the telephotographs have to be retransmitted because of lightning, static, and other troubles” AT&T abandoned their its first system altogether in 1933, having invested $2.8 million trying to get it to work.

In the works at Bell Labs, however, was a second-generation “picture sending apparatus" of an entirely different design, using all-new technology, that Bell claimed would transmit pictures faster and deliver copies “indistinguishable from the transmitted original.” But well into the 1930s, the picture agencies still were sending their photos to clients by auto, train, airplane, bicycle, or any means available, a built-in delay of hours and even days.The news photo services were still in a three-cornered fight though 1934, when AP startled its competitors by announcing what it called a $1,000,000-a-year Wirephoto system. It claimed that soon, AP newspictures would be in its client’s hands only hours after they were made. No start date was announced.

Not long after AP's announcement, the luxury liner Morro Castle flashed an SOS on September 8, 1934, from just six miles off the New Jersey coast. The ship was ablaze, her captain dead of mysterious causes, and a terrible storm raged. The ship’s firefighting equipment had been shut off. 131 passengers and crew would perish.Cautious air charter pilots stay grounded in vile weather, but International and Acme knew pilots with daring and courage who would fly - if the payment was generous enough - through just about anything. At dawn in two separate planes, INP and Acme photographers flew over the doomed ship and got dramatic pictures. AP had no pictures of the burning vessel and Acme and INP wanted to make sure everybody knew it.

Soon trade paper ads compared their aerial photos of the burning liner to the file photo AP offered of the ship in port well before the calamity, under a headline that mocked AP: YOU MUST FIRST GET THE PICTURE BEFORE YOU NEED A MILLION DOLLAR TELEPHOTO.

New Year’s Day, 1935, was literally the dawn of the “picture wire service,” and the most significant date yet in news photography’s coming of age in the United States. The Associated Press had adopted the AT&T system and inaugurated “Wirephoto.”

Invited guests were on hand to witness the birth of Wirephoto, which could carry high-fidelity pictures to multiple receivers over a national leased phone network. Solemn engineers tweaked dials and tinkered with an eight-foot panel full of bulbs, wires, and wavering needles.In 24 newspaper offices across the country other guests watched technicians tinker with switches, generators, and lathe-like receivers. Lights flashed, needles swung, and then a whistle blew. A stentorian voice over a loudspeaker announced: "New York speaking. This will be the first official roll call for Wirephoto."That first picture showed half-frozen survivors of a plane crash deep in the Adirondack Mountains, and the 24 papers received it simultaneously on a 10,000-mile leased circuit, proof that photographs, not just words, could be delivered by wire.

News photography, at last, was catching up with print. Editors suddenly had both words and pictures of that same day’s events, and readers could see what was happening in the world at the same time they read about it. Editor & Publisher magazine that year began a regular column devoted to news photography. In his first column Jack Price wrote, "The snobbishness of the scribe towards the photographer is fast disappearing. Photography has a very definite place in modern journalism."Any of AP’s 1,200 members could have Wirephoto if they shared its costs, based on their city’s population. In New York in 1936, Wirephoto cost $150,000 a year, and only one of New York’s eight daily newspapers, the tabloid Daily News, thought it worth the investment. Every paper on the leased photo network could transmit as well as receive photos, enabling them to share their own best pictures with other AP member papers on the “party line” leased telephone circuit. By March 1935 Wirephoto was carrying about 70 pictures a day.

Conspiculously absent from the new Wirephoto network were Hearst and Scripps-Howard newspapers, although fifteen of Hearst’s papers and six of Scripps Howard’s were AP members. Publisher Roy Howard had lobbied against the Wirephoto project at AP’s annual meeting. AP's general manager Kent Cooper was the force behind AP's launch of a photo service in 1928, and now, he was pushing the newest photo delivery technology on a skeptical AP membership. Both Hearst and Howard huffed that wirephoto would be a needless extravagance, and sure to lead to ruinous competition, all for the sake of "pulling A. T. & T.'s $2,800,000 chestnut out of the fire."The Scripps and Hearst organizations, as well as Wide World, owned by The New York Times, had been working on their own photo transmitting and receiving machines since AP’s announcement in 1934. INP called theirs "Soundphoto," Acme was "Telephoto;” Wide World was "Wired photo."

A January 1936 AP advertisement in Editor and Publisher magazine rhapsodized about Wirephoto’s first year: “Eighteen thousand pictures, traveling 180 million miles, made it possible for the news-hungry public to see, with the keen eyes of the camera that misses no detail, the what and how and why of everything that was news while it was news. The result of a year of Wirephoto is a new kind of reporter, a newsman trained to see news in terms of pictures which can be delivered an hour from now instead of tomorrow, or next day.”

Before its own electronic delivery system was up and running Acme tried to stay in the game by using airplanes to deliver its pictures. And two things things bought the company time. AP’s photo reception quality sometimes left much to the imagination. And Acme’s Fred Ferguson had scored a coup when he secured exclusive rights to all photographs taken of the Dionne Quintuplets, born in 1934, through their fifth birthday.The five cute, identical girls, the first quints known to have survived from birth, had grabbed the world’s attention. They drew more visitors to Canada than Niagara Falls, and offered an upbeat distraction in the depths of the Great Depression. The public loved quint pictures, and only Acme could provide them, so editors retained Acme’s photo service while the company perfected its own photo transmitter/receiver equipment.

By the time quint fever abated in 1936, Acme had developed its own picture machines, more sophisticated and reliable than AP’s, and capable of better quality. Photos were transmitted to subscribers on a limited basis, and “Telephoto” was put through a successful test at the 1936 political nominating conventions in Philadelphia and Cleveland.Three major photo services were still slugging it out in 1948, when Acme, AP, and INP assembled crews in Philadelphia for the Democratic National Convention. Harold Blumenfeld, always thinking "speed," located Acme’s workroom right inside the convention hall, enabling Acme to put pictures in client hands less than 30 minutes after they were taken. AP and INP were slowed because they had located workrooms off-site. AP at The Philadelphia Bulletin, a mile and a half away, and Hearst’s INP at the University of Pennsylvania, a quarter mile away.

AP and INP’s response was stopped cold for awhile after President Harry Truman arrived at the hall and the Secret Service locked down the building for a time, making it impossible for AP and INP film messengers to even get film out of the hall.Dick Sarno, head of Hearst’s INP picture operation, was so impressed with Acme’s quick turnaround time that he appeared at Acme’s door to ask Blumenfeld if William Randolph Hearst, Jr., could come see how they did it. Young Hearst got a guided tour.In 1951 Scripps president Roy Howard persuaded a reluctant United Press management to make 27-year old Acme Newspictures a part of UP, to better match pictures and words and more smoothly compete against AP. UP president Hugh Baillie had resisted such a move for years, fearing that establishing a network of picture bureaus would diminish UP’s profits. Boyd Lewis later wrote, “The UP, which should have [been competing] on even terms with AP, had declared dividends for its executives for years -- by avoiding picture investment.”

Mims Thomason was named UP Newspictures general manager and Frank Tremaine, a distinguished reporter and editor, the assistant GM. “I didn’t even own a camera,” Tremaine says. “So there we were – two amateurs thrown in on top of a bunch of pros. It took a while for [word] Unipressers around the world to accept pix people as one of them.”The new United Press picture network was not as extensive as AP’s, and expanding it across the country became a top priority. A pair of brilliant UP engineers, Jerry Callahan and John Long, came up with Unifax in 1954, a revolutionary machine that needed no operator. Pictures could be viewed as they came in on a continuous roll of inexpensive electrolytic paper. Suddenly UP’s picture service was within economic reach of the country’s smallest newspapers and television stations. Unifax would soon bring UP pictures into 400 cities, allowing UPI to expand its leased photo network, and fill the great gaps between the East and West coasts.

Frank Bartholomew, UPI's last reporter-president, took over in 1955 obsessed with bringing Hearst's International News Service (INS) into UP. He put the “I” in UPI in the spring of 1958, when UP and INS merged to become United Press International. (UPI).Hearst, who owned King Features Syndicate, received a small share of the merged company. Lawyers on both sides worried about antitrust problems if King competitor, United Features Syndicate, remained as a part of the newly merged company. So UFS was made a separate Scripps company, which deprived UPI of a persuasive sales tool and the eventual river of gold generated by Charles Schulz’ wildly popular Peanuts and other comics.

The new UPI now had 6,000 employees and 5,000 subscribers, 1,000 of them newspapers, though a decline in the number of the country’s newspapers had begun. In cities that had two or more papers, the afternoon dailies, a majority of them UPI clients, were often the first to throw in the towel. There was also stiff new competition from “supplemental” news services created by major newspapers, including The New York Times and The Chicago Tribune,which had begun marketing their own news content to other news organizations at bargain-basement prices. AP was a publishers' cooperative and could “assess” its members to help pay for extraordinary coverage of such things as wars, the Olympic Games, or national political conventions. But UPI clients paid only a fixed annual rate; they expected UPI to cover extraordinary events but UPI couldn’t ask them to help shoulder the extraordinary coverage costs.

UPI sold its services helter-skelter, charging clients what they were willing to pay instead of basing rates on the size of the paper’s market in twenty three of the largest U.S. cities. Newspapers typically paid UP about half what they paid AP in the same cities for the same services. The Chicago Sun-Times paid AP $12,500 a week but UPI only $5,000; the Wall Street Journal paid AP $36,000 a week but UPI only $19,300. Most papers paid less for UPI’s worldwide news and photo services than the salary they paid just one staff reporter.

Though UPI never faltered as a news powerhouse, it needed management and financial support from Scripps that it didn’t get. As UPI’s losses grew, Scripps focused on containing the losses instead of exploring new revenue sources. “The only bank we could do business with was Scripps,” former UPI president Rod Beaton told an interviewer in 1995. “They had one vision. UPI was to be a fully competitive alternative news service to the Associated Press.“[Scripps] wanted UPI for their newspapers and for their broadcast stations, period,” Beaton said. “ Beyond that, they weren't interested. The business was changing rapidly, so fast that we couldn't keep up with it. Hell's bells, we should have been the CNN.

There wasn't a way in hell we could do that as long as Jack Howard was on our board. Jack represented the broadcast interests of Scripps, and they didn’t want us doing that, period. Our ownership limited our opportunities sometimes.”Both Beaton and Charles Scripps, however, ignored entreaties from Bernard Townsend, a Scripps financial vice president, to explore the growing world market for business and financial information. UPI stuck to its basic business as the media landscape shifted and more nimble media companies found ways to profit from the communications revolution - a market that would enrich rival Reuters.UPI lost $5.3 million in 1978, and Scripps began looking for someone to take the company off its hands. The client list was robust, with 7,079 subscribers worldwide, including 1,134 newspapers and other publications and 3,699 broadcasters in the U.S. Scripps looked first to the journalism community, but the big players - among them The New York Times and the Times-Mirror and Knight Ridder chains – all said their shareholders would not want them investing in an ailing enterprise. News organizations that benefitted most from the fierce competition between two news services proved unwilling to help keep one of them in business.

E. W. Scripps had established a trust for his four oldest grandchildren, and by 1981 all were in their 60s. If Scripps simply folded UPI, the trust could face as much as $50 million in severance pay, pensions, and other costs. But if they continued to underwrite UPI’s heavy losses the trustees could be open to lawsuits by the heirs.Like washing and waxing a car before a sale so the customer doesn’t look too closely under the hood, Scripps even spiffed up UPI’s New York headquarters to impress would-be buyers. The news and photo departments were relocated and the first new furniture staffers had seen in years appeared, along with workstation cubicles that made UPI’s world headquarters resemble an insurance office. No longer could anyone eat lunch at their desk – but that policy was dropped when staffers actually started leaving their desks for lunch and their phones and the day’s business went unattended until their return.Reuters, a British-owned news agency, ran a limited newsgathering operation in the United States. Sensing a bargain, Reuters expressed interest in UPI, and its executives toured bureaus in the US and abroad, gaining intimate knowledge of UPI operations, before talks collapsed. But Reuters would be back. By 1982, after four years of trying to find someone to take UPI off their hands, the Scripps family members reached the end of their rope. They even considered giving the company to National Public Radio, which could have meant a UPI tax break for as much as $100 million. NPR nixed the idea. The company’s financial troubles seemed irreversible, and “ UPI had become such a hot potato,” one executive said, “that they were ready to toss it to anyone who would grab it." Grab it, someone did. On June 2, 1982, Scripps president Ed Estlow announced that UPI had been sold, to Media News Corp., a new company formed by an unlikely and virtually unknown pair of young entrepreneurs from Tennessee. Doug Ruhe, 37, and Bill Geissler, 35. They owned a small Nashville company that, it turned out, was barely meeting its payroll, an attribute they'd bring with them to UPI.

The two men had no news experience, and in time they managed to do to UPI what AP could never have accomplished – pillage the company assets and reduce a proud company to insignificance. Over the next 17 years after UPI was "sold" it would have four chairmen, 13 presidents, a fire sale of assets, ever-shrinking revenues, and a steady defection of clients. And twice it would seek bankruptcy protection.

Ultimately, and contrary to speculation at the time, Scripps didn't get even one dollar for UPI; it gave UPI away, and sweetened the deal by giving the new owners eight million dollars to pay off debts and shore up the anemic pension fund. “In a sense,” Charles Scripps later said, “we filled up the gas tank and sold it that way. So they had some working capital.”Scripps wanted no liability if UPI’s creditors forced the company into bankruptcy, and wanted to demonstrate that it had made every effort to give the new owners a reasonable chance at success. “It was not generosity as much as self-interest,” a source close to the negotiations said. “The main consideration was that Scripps didn’t want to get the business back in six months.”

Soon there were hints of money troubles. In 1983 UPI president Bill Small got a call from a friend, a vice president of The Chicago Tribune, wondering why UPI hadn’t paid the $100 owed for papers delivered to UPI’s Chicago bureau. By 1984 money was so tight that the phone company cut off bureau telephones for nonpayment.Ruhe and Geisler weren’t exactly wowing the journalism world. They had owned UPI for a year and a half when they tried to “wing it” in a forum where newspaper experience and maybe doing some homework would have been helpful: their debut before the convention of the American Society of Newspaper Editors.They did not invite any of their older and wiser UPI veterans onstage to help field questions. Will Jarrett of The Denver Post got right to the point: “What can you provide newspaper editors that AP cannot?” Neither Ruhe or Geissler, separately or together, could offer a good answer. The New York Times coverage was merciless: “without exception editors interviewed after the session were convinced that Mr. Ruhe and Mr. Geissler did not know enough about newspapers to make it worthwhile to subscribe to the [UPI] service.” Photo stringers helping UPI cover the 1984 Olympic Games in Los Angeles were surprised when a well-dressed fellow appeared, carrying a briefcase full of money to pay them in cash. Banks were no longer honoring UPI checks. Stringer Wade Byers remembers being told that “The owners were trying to sell UPI and it would send the wrong message if the company collapsed during the Olympic Games.”Other stringers around the country weren’t so lucky. They continued to provide pictures that UPI used immediately and submitted bills that UPI didn’t pay for weeks or months. Fed up with the long wait, many drifted away to the competition. Staffers had it slightly better:their paychecks still cashed, but UPI was slow to reimburse them for out-of-pocket expenses – cabs, meals, and such. American Express canceled cards issued to executives and bureau chiefs. UPI had come to stand for “UnPaidInvoice.”

UPI was so desparate for cash – in many cases barely able to meet the payroll – that Doug Ruuhe began selling off irreplaceable parts of UPI at fire-sale prices.

Assets UPI needed to sustain day-to-day operations were sold for less than the annual revenues they produced: the company’s stake in UNICOM, a worldwide commodities news service; its right to one-fourth interest in UPITN, a television news film service; the rights to its electronic data base; the right to market UPI’s stock price reporting service; and its priceless, 11.5-million image picture library. These transactions provided one-time cash infusions of millions of dollars but divested UPI of vital resources and revenues it needed to survive.

Perhaps the most capricious of all the dealmaking was the 1984 sale of UPI’s robust overseas picture operation to rival Reuters for about a third of what it was worth. So formidable was UPI’s European photo operation that UPI wouldn’t sell the picture service to any client who didn’t buy the news report, too.

Only a year before Ruhe had agreed when his senior staff told him that the foreign newspicture operation was so critical to UPI that it should be sold only as an act of desperation. Reuters had no photo operation of its own, and had predicted in a June 1984 stock-offering prospectus that it might acquire UPI's overseas operation for $7.5 million. Now, keeping the negotiations secret from even his most trusted executives, Ruhe sold the UPI foreign photo operation to Reuters for only 5.7 million, millions less than even Reuters thought they might have to pay just months earlier: $3.3 million in cash and $2.4 million in monthly payments over five years.The deal gave Reuters 24 functioning photo bureaus and dozens of its best photographers, plus a working distribution system and millions of dollars in long-term client contracts. It enabled Reuters to take a giant leap ahead of Agence France-Press, which at the time was trying to organize its own worldwide photo service. European controller, Charles Curmi, had learned that Reuters might have been prepared to pay far more for UPI, perhaps as much as $10 million. He relayed that information to Ruhe’s negotiator, Bill Alhauser, who warned him not to rock the boat since UPI was so desperate for cash. The deal done, UPI’s executive picture editor.Ted Majeski, was outraged. “If there was a buck in it,” he said, “these guys would cut off and sell your leg and still expect you to run in the Olympics.”UPI would later claim that its ledgers weren’t sophisticated enough to determine whether the overseas picture operation had been independently profitable. But Mike Hughes, the UPI executive editor and vice president in charge of the international division, had no doubts. The sale to Reuters, he said, was “the most idiotic deal that was ever made."

Had Reuters worked 24/7 to organize its own service, Hughes said, “it would have taken (them) three years just to put all the transmitters in place. I'd say a conservative guess is that we saved them $20 million and five years." UPI, of course, still needed to provide foreign photo coverage for its domestic network. It could no longer direct foreign coverage or tailor it to UPI's needs. Using UPI’s former staffers, Reuters wouild now be provider of European photos to UPI. And as a part of the deal, UPI would furnish American photos to Reuters. In the final moments of negotiation Ruhe even agreed – against the anguished advice of key executives - to let Reuters compete with UPI in the U.S., selling its own photos to the larger U.S. newspapers. Majeski was openly contemptuous of Reuters’ ability to serve UPI’s needs. A major earthquake rocked Mexico City in 1985, and UPI was almost three hours ahead of AP with the story, but Reuters had not yet provided pictures. Majeski arranged a chartered plane and sent a photographer to Mexico City, who got sensational earthquake pictures for UPI clients. Majeski sent Reuters a bill for the charter.

Next on the block was UPI’s crown jewel: the picture library. Its 11.5 million images of events and personalities, some so old they were on glass plates, dated back to the Civil War. It is a priceless collection not just because of its size, but because of the “you are there” quality of its once-in-a-lifetime moments recorded by International Newsphotos (1912-58); Acme Newspictures (1923-52); Pacific and Atlantic Photos (1927-30) and United Press. The sale of reprint rights to the pictures was earning UPI more than a million dollars a year, using only four salesmen and no marketing program. The business department believed that a new electronic retrieval system and a marketing plan could double or triple that income. “Who cares about a damn picture library?” Geissler asked. In 1984 he sold it to the Bettman photo collection – by then owned by Kraus-Thompson of Canada - for only $1.1 million. It was called an “advance royalty payment” in a 20-year deal. Bettman gained exclusive control and proceeded to move the photo files UPI needed every day to Bettman’s New York office on 21st Street. UPI lost immediate access to its own archive and had to pay Bettman $35 every time it needed a copy of one of its own pictures, often several times a day. For a time it even charged UPI photographers $15 a print whenever they needed a print of one of their own photos to enter in year-end contests. Bettman split resales of UPI’s pictures, keeping 75 percent for itself. The owners needed cash. They seemed not to understand or care that they were selling a photographic treasure, although it is not difficult to imagine that the photo collection could have gone the way of UPI’s word files, which were sent to a warehouse and, after UPI failed to pay the rent, vanished, along with the warehouse. In 1966 a staffer visited the site and found an apartment building where the warehouse used to be.The fire sale of company assets had raised $10 million but in the process had reduced the company's annual revenuues by at least $7 million a year -- to $93 million a year from more than $100 million. UPI photo editor Ed Hart was assigned as liaison to Bettman after the move. The Bettman staff, he recalls, couldn’t grasp the meaning of UPI’s connection to the files. Bettman had never been a news service, and the Bettman staff was "totally unprepared to handle UPI’s requests for copies of its own pictures,” Hart says. “It was an adversarial relationship.” When the Duchess of Windsor died in 1968 and UPI needed a quick file portrait it couldn’t obtain one for six hours because Bettman’s overnight staffer wouldn’t let a UPI staffer come select one. Next day the Bettman staffer was fired.

In 1995 Bill Gates’ Corbis bought and is today preserving the Bettman archive – UPI’s 11.5 million images and the 5 million-plus pictures Bettman had accumulated since 1933. The undisclosed price was reported by Newsweek to be $6 million.While the company struggled to stay in business and UPI's loyal staff accepted a 25 per cent wage cut to help out, Ruhe and Geisler were hiring expensive consultants who did little but collect fees as high as $20,000 a month. The staff would have been scandalized to learn that the owners expecting them to make one sacrifice after another were paying a consultant more every six weeks than they made in a year. When UPI filed for bankruptcy in 1985 the court learned that UPI had collected employee payroll deductions, but had not forwarded them to the Internal Revenue Service or the employee credit union. In August 1990, many UPI staffers, including several senior editors, got pink slips, Senior executive Pieter VanBennekom sent a message to all bureaus. He would “miss those who left us,[but that] reshaping the staff is necessary to create the new UPI.” By November, saying it was on “life support, ” UPI imposed a 35% cut for remaining non-union employees. Staffers represented by the Wire Service Guild voted to accept the 35% wage cuts while, the Guild noted, “UPI tries to seek a buyer to keep the company alive.” By 1991, UPI was back in bankruptcy court, listing $22.7 million in assets but $65.2 million in liabilities.In 1998, Arnaud de Borchgrave, the former editor of the Reverend Sun Myung Moon's Washington Times, became UPI’s CEO, but by then UPI had lost virtually all its newspaper clients. It had retained some 400 radio clients, but in 1999 sold those contracts, too, to the AP.

By 1999 UPI ceased being a traditional wire service. "It is time to move on," Borchgrave said, and UPI would from that day forth exist only on the Internet. ”The world no longer needed two redundant wire services." In May 2000 what remained of UPI was sold to Moon’s News World Communications for an undisclosed amount. UPI was down to 157 employees -- in Washington, London, Latin America, and Asia – and only a few customers. Given the fact that Scripps gave the company away, one might wonder why UPI’s executives – who possessed the news experience Ruhe and Geissler lacked – didn’t try to buy UPI in 1982 when Scripps was paying someone to take the company off their hands. And if Scripps wanted to give the company away, why they didn't sound out UPI's loyal employees.Buying UPI, Frank Tremaine says, “was totally impractical financially. Even though the price was right, it took oodles of money to operate UPI and none of the top brass, which presumably included me, had the necessary resources.

The E. W. Scripps organization had sunk millions into the company to keep UPI afloat for years. They couldn't continue to do that, nor could they finance UPI executives to try to keep it going. Major publishers and broadcasters already had rejected the idea. It just wasn't feasible.”Bob Page said: “My regret, looking back on it, if I had known about leveraged buyouts, I would have put a group together. I said to Rod [Rod Beaton, UPI’s president] many times over that if they were going to give it away, which they did to Geissler and Ruhe, they should have given it to you and me. We wouldn't have screwed it up. I mean, we loved the company. They could have given it to all of us.” Today, the only mention of “UPI” in newspapers is likely to be found in the obituaries, since a considerable number of the nation’s journalists over 50 once worked for United Press International. “UPI never admitted to "going away," recalls photo stringer Harrison McClary. “They were still there, but from late 1993 or so anyone crazy enough to transmit (pictures) to them was not getting paid. They closed down most of their bureaus … and the people now working for them are not the same people from the old days” The decline of the once-great company “was like watching a parent die,” Ed Hart says, “From the time I was 17 years old, Acme, UP, and UPI was my family. I spent more hours with those people than I did at home.”

**6/2007 HAYNES' NOTE: KEROUAC'S USE OF UPI TELETYPE PAPER HAS BEEN CONFIRMED BY THREE INDEPENDENT SOURCES, DESPITE SEVERAL WEBSITES DESCRIBING THE MANUSCRIPT HAVING BEEN WRITTEN ON VARIOUS OTHER MATERIALS BY RESEARCHERS WHO LIKELY HAD NEVER SEEN, OR COULD NOT GRASP, THE CONCEPT OF A CONTINUOUS ROLL OF UPI TELETYPE PAPER.

Text excerpted with permission from Picture This! The Inside Story and Classic Photos ofUPI Newspictures, (c) 2006, Gary Haynes

A special thanks to Ed Hart for permission to reproduce historical photographs accompanying this article.

Note supplied by Ed Hart: Author Gary Haynes' date for the creation of Pacific & Altnatic Photos (1927) is incorrect. P&A, the offspring of the New York Daily News and the Chicago Tribune, was in business in 1925. The photo that accompanies Haynes' article that shows P&A staffers at a Christmas Eve party has the earlier date written on the print itself and that information was put there by my father moments after he made the print in the late afternoon of Dec. 24, 1925. Later, that date was independently confirmed by two of the staffers identified in the party photo caption. Haynes relied on Frank Tremaine for the start-up date but Frank never worked for P&A, Haynes ckaimns FT had a story from the New York Times with the '27 date but the New York Times never worked for P&A, either. Besides, P&A negtive captions now a part of the Corbis photo library also confirm the earlier date.